I’ve put up a link to my program for my Master’s Recital 2018.

All posts by sara

My Senior Recital – A Rite of Passage

Program notes from my Senior Recital

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (1756- 1791)

Violin Concerto No. 3 in G Major

The Violin Concerto No. 3 in G Major was the third of five violin concertos composed by Mozart in 1775 while living in Salzburg. He was only nineteen when he wrote them, already midway through his short life of 35 years. He had just returned from an extensive visit to Munich where he had been looking for work at higher wages than the 150 florins annual salary he was receiving for his work in Salzburg. Perhaps he was adding to his resume after failing to find a better position, or perhaps he encountered inspiration for the violin concertos while traveling. Either way, the final three of the five are considered some of his greatest masterworks of his six hundred compositions legacy.

The concerto has three movements: I. Allegro, II. Adagio, and III. Rondeau – Allegro. In the first brilliant movement, orchestra and soloist joyously converse. It was speculated by John Irving in his 2010 notes for the Australian Chamber Orchestra:

It is as if a drama is unfolding on the operatic stage. And that comparison is, in fact, quite apt, because the way Mozart handles form in his concertos bears a very close resemblance indeed to the forms of his operatic arias in works from the 1770s such as Lucio Silla (1772). Seen in this light, the concertos take on a new aspect: not so much a contest between a virtuoso soloist and an orchestra, but a dramatic interaction between characters on stage; a narrative rapidly unfolding through the rhetoric of gestures, some of them painted with a broad brush but, in the main, subtle interactions rather in the manner of a conversation.

The movement dabbles in chord changes to D major, and then D minor, and others, but it resolves completely to G major in a final recapitulation.

Johann Sebastian Bach (1685 – 1750)

Sonata No. 1 in G Minor

Johann Sebastian Bach was not widely known or fully appreciated during his own lifetime. The man we revere as one of the greatest German Baroque composers was a member of a large musical family. Although orphaned at ten years old. Bach had some opportunity to travel during his youth, and was exposed to wider European musical influences. His compositions reflect this musical sophistication. He overloads every melodic voice in his pieces with companion voices, not merely harmonic, or contrapuntal, but equally developed melodies that compete with each other, an innovative style at the time.

Bach’s family members included local luminaries who served as village and church music and choir directors, and were occasionally appointed to elevated positions by minor aristocrats. Bach followed in the family business, spending most of his life as a music director and organist, at one time receiving the patronage of Prince Leopold of Anhalt-Köthen who recognized his extraordinary talent. Leopold, as a Calvinist, eschewed the extravagant use of music in worship as false idolatry, and hired Bach to compose and direct primarily secular music. It was during this time (1717 – 1723) that the Sonatas, Partitas, Brandenburg Concertos, and other orchestral works were written.

The Sonata No. 1 in G minor is in most respects a Sonata da Chiesa (a Church Sonata); a four movement composition using a traditional fast-slow, fast-slow pattern. This type of sonata would be restrained enough to be appropriate in church, although it didn’t serve any liturgical function in the Catholic mass. It would more commonly be played as entertainment in a genteel setting.

Niccolò Paganini (1782 – 1840)

Caprice No. 20 in D Major

The dictionary defines a caprice as an impulsive action, taken on a whim or as a lark. The series of twenty-four caprices written by Niccolò Paganini between 1802 and 1817 may feel as if they are random dances of the mind, but in reality they are carefully contrived exercises — études designed to address every piece of a violinist from fingertip to soul. Paganini was a virtuoso and vigorously marketed himself as such. The caprices he wrote (but never played publicly) were his gift to artists who would aspire to bring their own craft to new heights, to his level. The Caprices are so comprehensive and difficult that they are a staple of the auditions required of students applying to every Master of Music program. Moreover, they are my rite of passage. For the last ten years or more, I’ve thought that when I can master even one of the Paganini caprices, I will honestly be able to call myself a violinist.

Each of the twenty-four caprices carries its own special flavor and challenge. I chose to play number twenty in the key of D major because it is so warm and beautiful. It comprises three sections evoking a simple day in the Scottish highlands. First, a solemn salute to the rising sun, a collection of rich notes that lie against a steady drone note that produces the characteristic bagpipe sound. If you break the drone note, you break the carefully crafted illusion of a lone piper on a mist-shrouded crag. After a gentle minute of this, an entirely new theme is entered, a frenzied center section, lasting about a minute-and-a-half. It feels like a meadow dance of the fantastic wherein bees, hummingbirds and deliciously graceful fairies frolic capriciously as trills and flying staccato tumble off the bow in sixteenth notes. Finally, there is a return to the piper – standing now on the sand mourning the loss of the huge red sun that at last, slips into the sea.

Maurice Ravel (1875 – 1937)

Tzigane

Not long after composing his jazz-inspired Violin Sonata, Maurice Ravel struck up a friendship with British-Hungarian violinist Jelly d’Arányi, the inspiration for his rhapsodic Tzigane. The title itself translates to “gypsy”, and the piece certainly holds true to its name. “This Tzigane must be a piece of great virtuosity,” Ravel told the violinist. “Certain passages can produce brilliant effects, provided that it is possible to perform them — which I’m not always sure of.” The piece premiered in London on April 26, 1924, and it is rumored that d’Arányi only received the finished score a day or two before the performance. At the inaugural London performance, the music’s gypsy flavor was enhanced by the use of a piano attachment called a luthéal, a relatively new invention that had only been in use since 1919, which caused the piano to take on the sound of a Hungarian cimbalom or dulcimer.

Tzigane opens with a lengthy quasi-cadenza for the solo violin which introduces and explores several of the themes to be encountered later in the piece. The entire first page of the violin part is played on the G string; a celebration of the instrument’s oft overlooked lower register. Next, the violinist introduces a passionate, chord-laden melody that grows increasingly animated and intense. As the music gradually climbs toward the stratosphere, Tzigane demonstrates the use of several advanced virtuosic techniques. The improvisatory feeling of the music is a reminder that Ravel incorporated many of d’Arányi’s improvised embellishments into the score. From a piano cadenza, originally orchestrated for harp, emerges the dance-like main theme, which Ravel presents in a series of variations, each more impressive than the last. The piece rockets to its finish, culminating in a dazzling exhibition of virtuosic techniques.

Johan Halvorsen (1894 – 1965) George Frideric Handel (1685 – 1759)

Handel-Halvorson Passacaglia for Violin and Cello

Spaniards originated the passacaglia musical form in the early seventeenth century, but Italians are credited with its development. The portmanteau “passacaglia” translates to street walk, a cadential interlude originally used to connect disparate pieces. It evolved throughout the centuries and most academics today will agree that a passacaglia’s defining characteristics are that its chords iterate over a ground bass and that it is frequently written in triple-meter. The mathematician in me sees the passacaglia as a microcosm of our lives. What are lives but a series of days, each much like the day before, yet each holding a variation? We live cycles as infant, scholar, parent, and elder. We grow in wisdom; cultivating social, emotional, and intellectual expression all on the ever-circling canvas that is the days of our lives.

George Frideric Handel wrote his Harpsichord Suite in G minor in 1720. He used sixteen variations over a ground baseline in his sixth movement, a passacaglia that I can only describe as relentless. Is the Handel-Halvorson Passacaglia for Violin and Cello merely an arrangement of Handel’s work? I don’t think so. I believe it has been extrapolated to the point that it stands alone on its own merit. It’s almost as if Halvorsen were a modern artist sampling the content of another artist. Halvorsen’s work uses tempo changes to destroy the “relentless” characteristic of Handel, adding emotional color and artistry. Where one could almost describe Handel’s work as pounding algorithmically on keys, Halvorsen introduces extended techniques that were not available in Handel’s time: Saltando, ponticello, artificial harmonics, and more. While Halvorsen certainly owes an unpayable debt to Handel, his Passacaglia for Violin and Cello is a unique modern work, using an entirely different and more sophisticated toolset than Handel could have dreamed of two hundred years earlier

Views: 6644

An Interesting Idea — Apprenticeship

I am always looking up my favorite performers, and checking out their schedules to see if they’ll be in Santa Barbara any time soon. Joshua Bell is really nice, he invited our violin studio to his concerts and posed for photos with us, like this one taken by our professor, Yuval Yaron.

I’d sell my soul to have Joshua Bell teach me in a master class at the Granada before a show, but he’s not someone with a lot of time. In fact the only way to get a lot of time with a first rate performer would be to follow in his or her footsteps as an apprentice.

Wouldn’t that be awesome to travel with Joshua Bell or Hilary Hahn? It would be even better if there were an apprentice program that allowed me to play in the back of the violins at each of their concerts.

Playing the violin is one thing, figuring out how to get around airports, concert halls, and rental cars is quite another. So I guess an apprentice would have to be old enough to drive, and maybe even 21, just in case we needed to go into a club. In my imaginary apprenticeship, the apprentice would be between the first and second year of a master’s program and she would have auditioned for an apprenticeship with the artist. And there would be a very large stipend. A girl can dream. Let’s see, I’m a third year Bachelor of Music major, so that’s two years until I’m ready to go!

Rather than the artist having to actually figure out any logistics, their agencies could take care of all of the details. If all of the agencies did something like this, it would become an accepted thing in the music world. Symphonies would make space for the apprentices without ever even thinking about it.

The apprentice system might also solve one of the fundamental problems with having a first rate teacher who still performs all over the globe. I am lucky that my UCSB professors and ensemble coaches are very dedicated, but I have heard that at some universities, the big name artist that draws the students to the school are often unable to keep lesson appointments because they are traveling. With an apprentice system, you could get your lessons on the road.

Imagine being on a ride-along with Sarah Chang and her mythical beast, Chewie. Right now, Chewie has to stay at home while Sarah goes off to play, but in my imaginary world, he’s be traveling with us.

Chewie looking miserable that I dressed him up in the Hawaiian shirt I got for him on my last trip!

— Sarah Chang (@sarahchang) March 21, 2016

Who else would be fun? Rachel Barton Pine is cool, and maybe she’d bring an extra Stradivarius from her foundation for me to play on. Or she could get me up to speed on the electric violin. She played a 6-string viper in Earthen Grave, now sadly disbanded.

I’d also love to travel with Itzhak Perlman. He’s going to play in Los Angeles on January 24, 2017, and I really want to see that concert. He’s going to be at Disney Hall. Maybe I could even sneak backstage and mention that he might be way more popular with a cute little apprentice.

Future apprentice with her own cute little doggie.

Views: 4805

We Miss You Max

Reger, A Centenary Retrospective

Max Reger lived just half of a lifetime, but he produced at least three lifetimes worth of work in his 43 years. On May 11, 2016 we celebrated the centenary of his death by sharing the magic of his life with our cozy audience in Lotte Lehmann Concert Hall.

Jeremy Haladyna, our tenacious advocate for newer music and champion of the UCSB Ensemble for Contemporary Music pushed ahead the quarterly ECM performance so that we could celebrate Max’ life on his very special anniversary.

The program focused on Reger’s chamber works — ECM is a chamber group, after all. We were fortunate to have two special guest artists play with our ensemble, Hiroko Sugawara did a fabulous job of bookending the concert on clarinet, and Christina Esser, mezzo-soprano, sang a selection of Reger’s charming Simple Songs. The lyrics are the sweet and simple part -these are stories about home and family, kittens and mice, laid against some devilishly enticing melodies. As a life-long fan of the hedgehog, I particularly enjoyed Der Igel, a warning to all to beware the Prickly-Coated One. But like the kitten, I stray ahead!

The concert opened with our professor, Jeremy Haladyna, accompanying Hiroko Sugara on the clarinet. Hiroko is not just a member of ECM, she’s a member of the UCSB faculty, teaching Japanese in the East Asian Languages and Cultural Studies department. I played clarinet for a few years in middle school band, so I have a little bit of appreciation for how amazing her playing is. She hides a great deal of breath control behind that lovely smile! The two played Reger’s Sonata for Clarinet and Piano in B-flat, I Moderato, op 107.

Dana Anex followed with a lovely solo, Prelude for Solo Viola, from Three Suites, op 131d, an excellent example of Reger’s foray into neoclassicism. She was followed by Kathryn Carlson, cellist, playing Peter Sculthorpe ‘s Requiem( for Cello Alone). The two solo pieces were tremendously moving. Haladyna chose to follow these solos with the Simple Songs, a wise move when your ushers don’t have tissue boxes to pass around for the tear-gathering.

I followed Simple Songs with a personal tribute to another “Max”. Sir Peter Maxwell Davies passed away just two months ago on March 14th. Davies was a composer and conductor, in fact, Master of the Queen’s Music from 2004 – 2014. I played Dances from his opera, The Two Fiddlers. Davies passed away on his beloved Orkney Islands, an archipelago in the Northern Isles of Scotland; my tribute piece is in the style of the Orkney Islands fiddlers. I really shouldn’t say “my” piece — I shared it with Petra Peršolja on piano. According to my mom, we were very well received, but she always says that. I know that we did a decent job because we played right before a brief intermission, and when I peeked through the curtains, nobody was running for the exits!

When the curtain rose after intermission ( Ok, I lie, we don’t really use the lovely and mysterious red velvet curtain. ), Petra Peršolja and Zachary Olea played Arvo Pärt’s Fratres I. I am looking forward to hearing them play more pieces like this together in the future. Zachary is a patient violinist and shows that he has a considerable understanding of what Pärt is trying to convey. Petra is one of our DMA students, and she is a very charismatic performer. She has the grace and ability to make everyone she performs with look as good as she does, even if that means holding back sometimes.

Our ECM classmate, Nick Mazuk, found a piece that he wanted desperately to play, and if nothing else works, desperation gets you everywhere with Professor Haladyna. So along with Dana Anex on viola, and Kathryn Carlson on cello, Nick treated us to selections from Vincent Persichetti’s Serenade No. 6, op. 44, including II. Barcarole, V. Intermezzo, and VII. Dance. It’s always a delicate balance when you put a trombone between two stringed instruments in a modestly-sized concert hall, but I was quite impressed that the strings were able to hold their own, and that Nick was able to exercise his instrument’s dynamic range without blowing the other instruments off the stage. Any of our composition students who happened to be in the audience hopefully were able to learn something last night about how to mix’n’match strings and horns without breaking anything.

At last, we circled back to Reger. Kathryn Carlson and Professor Haladyna played the Sonata in A Minor for Cello and Piano ,Op.116, IV. Allegretto con Grazia. It was truly lovely.

Zachary Olea returned for a second Arvo Pärt piece, Für Alina, this time with Danica Neuhause. I’ve included a link to the Wikipedia entry for the piece — I spent a little more time there trying to understand how the piece is put together. It’s my first recommended reading to you, my little audience, so go for it! What really sent me hunting for explanations was the dynamic tension the two violinists were able to maintain. I’d heard the piece played before with a completely different interpretation. I should mention that Danica very patiently turned pages for our pianists, and it was nice to finally hear her play!

At last, Hiroko retook the stage with her clarinet to close our show with three movements from Reger’s Clarinet Quintet, Op. 146, II. Vivace, III. Largo, IV. Poco Allegretto. Joining her were David Fickes, a talented junior transfer student we welcomed this year into our violin studio, and Zachary Olea (violin), Dana Anex (viola), Kathryn Carlson (cello), and Jeremy Haladyna, to conduct.

Have you ever watched your parking permit expire while you are trapped in a concert hall? It’s usually a gut-wrenching experience waiting for the final three movements of a piece to finish, hoping that the campus ticketeers have not come for your car. But honestly, I would have paid the price of a parking ticket happily just to keep listening to the quintet all night — it was that warm and comforting.

As things turned out, there was no ticket, my parents took me out to dinner, and I got a great night’s sleep, knowing that I had done my small part to make the Regar Year, 2016, a success. To find out about other Reger Centenial Festival events go here and here.

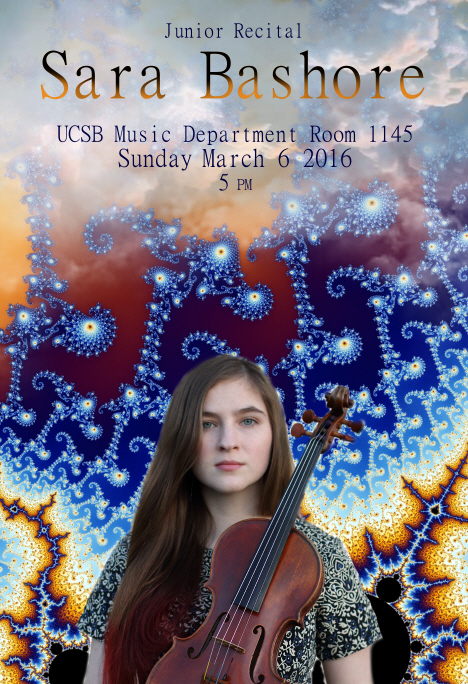

Views: 6304Program Notes from My Junior Recital

My Junior Recital was a resounding success! Thanks in particular to those who drove up from Los Angeles. I am including the program notes from my program here for those who want to listen on the CD.

George Frideric Handel (1685 – 1759) completed his Sonata in D Major, Op. 1, in 1750. This masterwork was his final violin sonata, published posthumously. The first of four movements is a sweetly plaintive Affetuoso decorated a climbing arpeggio and gentle trills. Next, fingers dance across the violin as the brilliantly vibrant Allegro invites us share in the happiness of a joyous life. Handel’s Larghetto suddenly breaks that the mood with a rolling tidal theme of loss, loneliness, and pain. Soon enough, a brightly transitional Allegro brings resolution.

Ludwig van Beethoven (1770 – 1827) published his Romance in F Major, Op. 50 in 1805, although it was likely written and performed several years earlier. A microcosmic piece of few extremes, it connects the listener to the breezy pastoral experience of a simpler time while examining the richness of modest aspiration. Beethoven is perhaps coercing us to smell all the flowers and enjoy each sunset while we can.

Johannes Brahms (1833 – 1897) wrote twenty-one charming Hungarian dances during the first half of his life. Most of the dances are not entirely original, but capture and embellish traditional Hungarian folk themes, recasting them to a variety of instruments and orchestral configurations. Brahms’ work was contagious and many of his contemporaries and successors further modified and enhanced the dances to the point that there is now an arrangement for virtually any instrument you can name. When No. 1 begins, we imagine lovely ball gowns sweeping parquet floors under crystal chandeliers. When No. 1 ends, we find ourselves luridly dervish-spent, sleeping in the haze of a bonfire. It’s a dangerous three minutes.

Frédéric François Chopin’s (1810 – 1849) Nocturne No. 20 in C# minor was written for Ludvika, his elder sister, in 1830. The Nocturne expresses grief and lament with a depth and purity beyond expectation, and as a result, the unrelenting raw, emotionally haunting music has been featured in several important films. Biographers suggest that Chopin’s artistry in infusing sorrowful passion into his works was a byproduct of his challenging health problems, displacement from his homeland, and troubled personal relationships. Virtuoso Nathan Milstein’s (1903 – 1992) arrangement for violin is true to the original, and wonderfully tight – Milstein was well known for his desire to perfectly articulate each note.

Pablo de Sarasate (1844 – 1908) composed elaborate show pieces primarily to exhibit his amazing mastery of technical skill on the violin. Navarra, Op. 33, Sarasate’s ‘Spanish Dance’, was written for two violins. With an ego big enough for two, some wonder jokingly if Sarasate didn’t somehow intend to magically play both violin parts at the same time. The somewhat stereotypical Spanish dance flavor provided by Sarasate is jota in style, but the finish is bigger, replete with fiery bowing.

Béla Viktor János Bartók (1881 – 1945) was the inspiration for my dance-themed program. Recognized as one of the founders of ethnomusicology, Bartók researched, collected, and studied Magyar folk music. He incorporated it into his work along with the asymmetrical rhythms of Bulgarian dance creating a unique style. Bartók’s success as a composer comes from research-based use of genuine elements. Romanian Folk Dances comprises six distinct movements (dances) of Transylvanian origin translated as: Stick Dance, Sash Dance, In One Spot, Dance from Bucsum, Romanian Polka, and Fast Dance.

Whew!

If you were at last night’s UCSB University Chamber Orchestra and Chamber Players’ concert, then you know what I’m talking about when I titled this post, “Whew!” The program packed a punch for player and audience alike with an often frantic pace and challenging complexity.

Robert Koenig, as the Director of the Chamber Players, once again showed his savvy in matching players to pieces. It’s our first big concert of the year, and we have many new freshman and transfer students on our Lotte Lehmann stage.

The show opened with Molly on the Shore, a Percy Aldridge Grainger piece. I did a little research on Grainger, and I’d like to do more because he sounds like quite the character, simultaneously engaging and repelling. If what I’ve read is true, he was not the most politically correct composer, in fact, some would consider him “merely” a glorified arranger. This could be said of Molly at the Shore with its mingled Irish reels but for the genuinely unique result — a melody that twists, interrupting itself oddly. In my opinion, the key to interpreting this piece is that it must remain at all costs, danceable. This is a piece I would like to hear again because “You just can’t have too many clarinets!” as my middle school band teacher, Cynthia Snyder, was fond of saying.

The second chamber group to perform was our Young Artist Piano Quartet. They played the Brahms Quartet in G Minor which I had heard earlier in the week in Geiringer Hall during a master class with Sunny Yang of the Kronos Quartet. I wrote about it here. I can honestly say that Brahms sounds much better in the larger Lotte Lehmann Concert Hall.

The last of the UCSB Chamber Players treated us to Ferenc Farkas’ Early Hungarian Dances. Individual dances in each of five short movements build the intensity. Each player was given an opportunity to showcase his or her skills, reminding all of us that matching players with pieces is probably an extremely challenging task. Flute, oboe, clarinet, horn, and bassoon are warmly suited to bring us these fireside dances that defy the encroaching winter.

After a brief intermission, the Chamber Orchestra took the stage. I’m a little biased here because I was sitting up there in front of a section of violins, but I think our Overture to Candide was very well received. Then, as the strings took over, playing Mozart’s Salzburg Symphony No. 2, I felt the audience tighten their attention, hopefully appreciating our nuances and even bowing.

Then it was time to regroup with our woodwinds, percussion, and brass to play Dvořák’s Symphony No. 8 in G Major. I’ll be honest, it is a complex piece by any measure. A violinist burns about 170 calories per hour if you trust a consensus of random web sites. Last night, I’m estimating that number was closer to 300. “A lesser orchestra might have crumbled”, I whisper to myself.

The piece is sometimes described as “pastoral”. I guess that’s true if the cows are blowing around in a fifty mile-per-hour gale and the grass has been trampled twice over. Or maybe we just played it a little faster than most, you know, because we can.

It’s a shame that our attendance was a little lower than usual — I think maybe Thanksgiving is coming too fast this year and people are busy. Speaking of thanks, Karen Yeh and Brent Wilson have done an admirable job bringing our newest students into the fold. I’m looking forward to great things for our winter and spring concerts.

Views: 5460

Weaving the Backstory with Sunny Yang

Sunny Yang: Color is Everything

Last Friday, in UCSB’s Geiringer Hall, fans of music, new and old alike, were treated to a master class featuring Sunny Yang, cellist of the Kronos Quartet, On the hotseat, our own music department’s Young Artist Piano Quartet playing Brahms’ Piano Quartet No. 1 in G Minor.

The Young Artist Piano Quartet is the graduate scholarship quartet in residence at UCSB, and the members are some of our best and brightest. They include:

Leslie Cain – piano

Youjin Jung – violin

Jordan Warmath – viola

Larissa Fedoryka – cello

A master class is a wonderfully terrible experience. The performers strive to impress a luminary, all the while knowing that any peccadillo is going to be fair game for criticism and correction. There’s almost a temptation to leave a breadcrumb trail of errors as a defense mechanism. At the same time, the audience is listening ever so carefully, waiting for problems and trying to pick out which aspect of the performance, which little failure the expert will select to discuss. No matter how hard you try, there is no perfection in a master class. Ever.

Sunny Yang is currently the cellist with the Kronos Quartet. She holds a Master of Music degree, earned at USC as a student of Ralph Kirshbaum. Her first order of business was to put the quartet at ease with her embracing smile. Then she chose to focus on the variety of emotions the piece presents. She asked pianist Leslie Cain to recall one of her sweetest emotions of childhood. Then she asked Larissa Fedoryka about what she was thinking and feeling. Larissa took a moment and replied that she was trying to convey deep sadness. It was then that I realized how difficult it can be to name the emotions we bring to music.

I thought back to elementary school, and our fourth grade lesson on vivid verbs. Each student would try to outdo the next with a more specific word. If Jack went to the store, Alissa walked, Danny trotted, Jace tumbled. When Miguel had juice, Jimmie drank, Natalie swigged, and Cody guzzled. I realized it’s like that with music. What I had been thinking of as merely sad is really drizzled with poignancy or haunted with elusiveness, and happy becomes crystallized with joy, twinkling with tenderness, or cloying with sweetness.

Next, Ms. Yang talked talked about timing, and how each individual player must give time and take time from the others. Again and again she spoke about how to put “color” in the music at the cost of technical perfection. She asked Youjin Jung to play a pair of notes on alternating strings repeatedly. A first tendency is to repeat the notes with equal pressure, equal bow angle, equal time. In reality, we can alternate those same notes in hundreds of different ways.

Ms. Yang complimented Jordan Warmath on her ability to communicate with the cellist and violinist, and discussed the difficulty of including the piano in the the circle. She suggested that while dynamics must be appropriate to the emotion, they are also one of an ensemble’s best ways to signal changes in mood, and that the piano, with its greater dynamic range, can share its dynamics to widen the circle.

What occurred to me as Ms. Yang spoke is that there are a very limited number of traditional fancy foreign words that composers have at their disposal, and that timing, dynamics, and mood can quickly become unreadable if the composer is extremely specific. And suddenly I had the great revelation that we aren’t supposed to be technically perfect — that we, as artists are responsible for supplying the gradations that would have only cluttered up our manuscript. The music is just the outline, we must bring our own story.

When I was little, my coach, Yi Huan Zhou, would tell me micro stories to match the music I was playing. In one, a little girl runs away from home and becomes afraid. In another, the little girl fails her spelling test after staying up all night, then realizes that it isn’t very important at all.

I think we, as members of an ensemble must also create stories, not just images of joy or sorrow, but entire stories. More importantly, we must share our stories with each other.

When the violinist chooses to interpret a phrase with anticipation, and the cellist, with trepidation, they should be very specific about the emotions they intend to convey, and discuss them by telling a tale. Then the pianist won’t be inspired to jump in with enthusiasm, when cajoling is what’s called for, and the cellist will tiptoe rather than stomp in. Color balancing color.

What I learn in this master class is that color is everything, and that without sharing the emotions we bring to a piece, we have only colored our own thread, we haven’t really woven a collective back story. The colors of our story must entwine with the colors of others if we want to present the audience with a cohesive emotional understanding of our music.

Views: 11722They Came to Play.

On Sunday morning, November 8th, UCSB dorm residents and members of the Isla Vista community were treated to a remarkable concert. Carillon students from UC Berkeley visited Storke Tower and played a recital program that sent the peal of carillon bells for miles in every direction.

There are two ways to listen to a carillon concert. Up close, and not so close. If you are, by some extreme of luck, able to go inside the tower, you will hear the machinations of the carillon as well as the music of the bells. It reminds me of the ballet. When you are on the stage, you hear the thunks, cluncks, and slides of 100 (or more) pounds of dancer hitting the floor again and again. But if you are across the orchestra pit, a mere 50 or 100 feet away, you only hear the strings, the woodwinds, the brass, the percussion. In the tower, things can be noisy because the musician is banging his or her fists on wood and although the chime of each individual bell spreads out as it leaves the tower, while inside the tower, the bells are loud and the echos are powerful.

UCSB’s Storke Tower sits in a lovely plaza with a reflecting pond. There are wide stairs into the plaza, which is lower than the surrounding grounds, and on Sunday, there were several people lounging about on the stairs enjoying the concert and the day, which was perfect for bells. I listened from a cozy UCEN nook. Outside the plaza, and off campus, my roommates were also enjoying the concert. The most wonderful thing about that heaviest of all musical instruments, is that you don’t go to the concert, the concert comes to you.

The four UC Berkeley musicians, Leslie Chan, Kunal Marwaha, Anders Lewis, and Felix Hu played a variety of selections, including my favorite, Londonderry Air, arranged by Sally Slade Warner. I wasn’t able to record it, so the link is Stacey Yang playing similar version on the University of Sydney War Memorial Carillon. In fact, I found an unexpected number of carillon videos, and although I have midterms coming up I found time to watch more than a few. My favorite was Jeff Le (class of 2008) playing the Harry Potter theme at the University of Rochester Hopeman Memorial Carillon.

I’m now more than a little interested in trying my hand at the carillon. I haven’t had the good fortune of going up Storke Tower for a tour — every time my email tells me that a tour is offered, I’m too late to reserve a slot. And of course, if you follow my posts here, you know I’m all about the post-concert reception cookies. When you are at home and the carillon concert comes to you, you have to bake them yourself!

Views: 12558Azeem Ward

Welcome to Azeem Ward’s Recital Preview!

My friend and orchestra-mate Azeem Ward woke up the other day as famous guy. It turned out that just about everyone who’s anyone in Great Britain is interested in attending his senior flute recital. And with good reason — his recital promises to be one of the best of the SoCal recital season! Also, there will be cookies. I told my mom to bring some extras.

Since Azeem has a handy-dandy Facebook invitation page, I already know what he’s likely to play even without an early-release program. So without further ado, here’s the line-up:

François Devienne Concerto No. 7

François Devienne was born in 1859 to a saddlemaker in Joinville, Haute-Marne, in the north-east of France. As the last of fourteen children, Devienne was likely free to choose a career path. A stint in the church choir led this tireless man into a path that led ultimately to the founding of the Conservatoire de Paris. He died at the age of 44, perhaps as some say, from overwork. In his short life, he wrote instructional materials as well as hundreds of works for flute and other instruments.

If you haven’t heard François Devienne’s Concerto No. 7 in E Minor, you are missing out on a wonderful piece. It’s a frolicking tune that will leave you feeling more cheerful than you’ve felt for a while. You will whistle it in the car after hearing it once, the themes of the first movement are that catchy. But don’t let first impressions sway.

The sweet and melodic Allegro leads into a gentle and almost tender Adaggio that gradually increases complexity, rounding into a sea of romantic lyricism that takes your breath away. But Azeem will still have breath left, and you will be left wondering what the rest of the concert holds!

Maybe there will be a cadenza, I hope so. We’ll have to wait and see!

The closing movement is Rondo Allegretto Poco Moderato. As Poco Moderato as you can get with flurry after flurry after flurry of 32nd notes. Were you invited to Azeem Ward’s Senior Flute Recital? Poco Moderato at the speed of light may be why.

Philippe Gaubert’s Sonata No.3 in G Major

Philippe Gaubert was born 20 years after François Devienne, and lived well into the middle of the 20th century. This celebrated artiste was Principal Conductor at the Paris Opéra, a composer, and Professor of Flute at the Paris Conservatory. While individually not the most inventive of composers, his work draws from and reflects the rich and fully developed musical tapestry originating toward the end of the late romantic period. Gaubert’s Sonata No. 3 was composed in 1933.

The Allegretto opens the sonata with a peaceful and relaxed exposition. There is only the slightest hint of the complexity we will soon enough encounter. This soothing movement ends on an optimistic high note.

The sonata’s second movement begins nicely enough, as well. It is an Intermède Pastoral, sweet dinner music Très modéré , however it soon takes a turn into a slightly more haunting style. It’s a winding piece layered with infinite patience. It asks us to believe that there are answers out there, answers to the big questions about creation, meaning, purpose.

Although we follow each nuanced ribbon, each tangential thematic idea, we are eventually left with even more questions about the nature of being than we started off with. In this sense, the sonata has a much more introspective appeal than most you will hear, because what you bring to the piece is a large part of what you will receive from it.

In this spirit, the final movement, styled as Joyeux Allegretto, reaches out to us. Why must there be answers? Why not just celebrate the day, the sunshine, the grasses, the rain, the night? And celebrate it does. But for those of us paying close attention, there is the slightest element of doubt, because, hey, complexity is fashionable.

David Roitstein’s Flautas

David Roitstein, unlike most composers, is alive and kicking, and actually working. He is currently the Jazz Program Director at CalArts (California Institute of the Arts) in Valencia, California. A pet project of his is The CalArts Jazz CD Project, a professionally produced collection of student works created at Capitol Studios. Yes. In Hollywood.

So wow! Roitstein’s Flautas are spicy, fresh, and warm. A perfect complement to the beautiful Santa Barbara sunshine. In fact the piece should really be about sunshine. Those flutes just push and peek through the clouds, then they slither in dancing on their tango toes. When 100,000+ people want to attend your recital, there is temptation to move the party to a larger venue. But that would be a crime against Flautas! However big the sound, the piece feels genuinely intimate to me for some reason. I can hardly wait to hear what sort of interpretation Team Felber comes up with. For those of you not in-the-know, Jill Felber is the Professor of Flute at UCSB, and she’s currently coaching the mega-star known as Azeem Ward.

Greg Pattillo’s Three Beats for Beatbox Flute

There are very few reasons to live in New York City. Just about every bi-coastal I know is going mono-by-the-beach because they’ve finally figured out that it doesn’t snow in coastal SoCal. But if there were just one tiny reason to stay in NYC, that might just be Greg Pattillo.

Every artist has a tagline on their website — a select snippet from a major publication which is lauding them, hailing them, celebrating them — you get the idea. Greg Pattillo’s line is lauded by The New York Times as “the best person in the world at what he does.” I know, right? Has the New York Times not heard of Azeem Ward? Seriously though, if you ask Azeem, and I’m not speaking for him here, but he just might agree with the New York Times. Pattillo is good. He’s introduced a sub-genre where no sub-genre has gone before.

When I was little (ok, I know I’ll never be more than 4’9½”) I slept with my violin. It was part of me then, and part of me now. I can only think that Pattillo has that same relationship with his flute. He slept with it, breathed with it, and the sounds of his life were etched into it. He explodes with that sound, not flute music, but with life.

Three Beats for a Beat Box Flute is amazing beyond belief.

Azeem hints that he will premiere original works!!

I’ve hear some of his original works, and I know there is no way to prepare. Azeem also mentions that he doesn’t play in a void. Here are some fellow musicians who we can hope to see in his senior recital:

- Adriane Hill

- Rachel Ricard

- Sylvie Tran

- Catherine Marshall

- Nick Diamantides

- Robert Johnson

- Kathryn Carlson

- John Scoville

- And couple “Guest Artists”

REFRESHMENTS.

Click here to donate to the UCSB Music Affiliates by Mail

Views: 10566

Dame Ethel Mary Smyth’s Double Concerto for Horn and Violin

The First Feminist Composer, Ethel Smyth

Until earlier this year, my sole experience with turn of the century British feminist history was a footnote in my high school AP European History book. So when asked about Emmeline Pankhurst on the AP exam, I would have been out of luck were it not for the Sherman Brothers’ “Sister Suffragette” lyrics that I’d remembered from the movie-musical, Mary Poppins.

“Sister Suffragette” is a high-energy, shower-worthy tune, with lines like, “Our daughters’ daughters will adore us, and they’ll sing in grateful chorus, well done, Sister Suffragette!” Down in the less catchy zone of the lyrics is the phrase, “Mrs. Pankhurst has been clapped in irons again”, a reference to one of the leaders of the British Suffragette movement. So I aced that question on the AP exam. Fortunately, I wasn’t asked to name the real anthem of the suffragette movement, as Mary Poppins offers no help there.

That honor belongs to “The March of the Women”, written by composer, Ethel Smyth, with lyrics by Cicely Hamilton. Smyth dedicated her song to the Women’s Social and Political Union, and with help from Emmeline Pankhurst, it was adopted as the group’s official anthem. Ethel Smyth was a rarity – she was not just one of the earliest female composers, but one who’s work is inspired and infused with a feminist agenda.

I will be playing Smyth’s Double Concerto for Violin and Horn in the not-to-distant future. I haven’t been able to find much about it, so I have written some program notes just for myself.

About the Double Concerto:

Dame Ethel Smyth’s Double Concerto for Horn, Violin and Orchestra/Piano is a challenging piece by any measure. It runs close to a half an hour, and is joyous, somber, and even frilly in some places.

I Allegro Moderato

The double concerto opens sweetly with a wistful, aspiring theme that says, “Here you have it!” as if we are to undertake a challenging task that will involve many different approaches. We are fresh to do our work, we will rise to the challenge. Small successes are greatly celebrated, while a brief failure or two are swiftly and softly mourned before the task is again undertaken. In some ways, we feel as if we are solving a five thousand piece puzzle. Much examination of each piece, pairing by color, sorting by shape, and grouping smaller sets into larger, we begin to recognize a forest, then a granite-faced cliff, and a small town town emerges in the background. As the puzzle comes together, we creep into the landscape ourselves and try to peep around a corner. But we realize that it is all an illusion.

II Elegy (In Memoriam)

Smyth’s elegy is quite restrained. I wish I could have stepped inside her mind to understand what she was trying to describe. It’s not a dirge or a funeral march, its a gentle lament. If it weren’t for the dynamics, I fear the piece would be a washout. But with the right dynamics, it does feel like a rainy day with thunder in the distance. I can just hear pages of yesterday’s newspaper fluttering almost inaudibly, blown against a screen door that is no longer slamming now that the wind has died down. I wonder if Dame Ethel was too optimistic and happy to write a properly morose elegy, I’ve certainly heard much more depressing music than she seems able to muster.

III Presto

There is pageantry of dervish proportion in this runaway march-flavored finale. What surprises me is that the movement has a sort of Disney feel to it for most of its approximately ten minutes of playing time. The horn and violin separate a little more in this movement, as if their individual stories have somewhat independent outcomes. The horn urges the violin to follow, and they do play together for a while before diverging. The violin returns to seek safety in the sand while the horn sets sail for the big wide world. It’s an altogether a fitting finale for such a wonderfully virtuosic pairing of instruments.

Views: 8678